She lay coiled in her blanket on the classroom floor amidst nineteen lyrik-sisters. The moonlight gleamed on the rustling hamster habitat and the softly burbling fish.

The door to the room the assistants shared stood silent and closed. There’d been a thin strip of light under it. It now was dark. Andromache turned on her back, pushing the blanket off. She wanted to be cold and uncomfortable to prevent drifting into slumber again. The classroom clock’s numbers, dull red: 23:52.

She pressed her hands together for patience

23:54. 23:58. 24:00.

At 24:01, she listened hard as hard. Nineteen slow breaths. One silent door. 24:02, she rose as noiseless as a deer in the woods. Her basket in her cubby had her pink sandals and her shawl. She stole to the door, pressed open the latch.

She wanted to put her sandals on inside but struggled against the psychs forbidding her, twisting against the discomfort of wearing them indoors, the mental itch, the fidgets crawling up her muscles. Her face a pained rictus of lips and teeth and closed eyes, she gave up with a hiss and donned them outside, the spams instantly subsiding. It would be quieter there instead of on the flexcoat flooring. Teacher’s sandals always made a smack smack smack. Andromache wished for silence. It was her will only. Hers alone.

She crept along the building to the oak grove. She knew there were cameras and security, but she also knew most of the efforts guarded the campus perimeter. On campus, it was peaceful and quiet. At night, what girl would leave her lyrik? Such thoughts were impossible.

Dryad-like she melted through the trees. She scurried across deserted quadrangles, closer to the Incubatory, its domes, round walls, and tall windows soft yellow with low spotlights. Its high doors, its grand foyer.

She didn’t go the front way. Someone manned the desk all night; technicians worked in the front corridor labs. But Andromache’s eyes were always open, and numbers stayed with her like friends. Around the side of the Incubatory, by beds of irises, was a service entrance with a keypad. When she was a six-year on garden duty, men came and went, tapping out the number six-six-three-five-four-nine, over and over.

She put her hand on the keypad.

“Sister Andromache!”

She jumped, spun.

“Briseis,” she hissed, eyes narrow, fists balled instantly.

“What are you doing here?” Briseis stepped back, raising her hands.

“Not sneaking after me.”

“Sneaking! You cannot be here.”

“Why are you here?”

“I’m First Girl. I cannot let you be here alone. I woke as you left. You were fast, but I followed.”

Briseis breathed quickly, and her hands wrung and soothed each other. Andromache stood rigid, yellow-silver in lights on the Incubatory wall. Then she whirled, moving her fingers over the input.

“Sister doula!” Briseis cried.

Andromache pulled the door, wiped the pad and latch with her shawl, and darted in. Briseis, hesitating, followed as the door swung closed.

She hobbled foot to foot, taking off her sandals, then raced after Andromache, who kept hers on, walking hunched and angry on her toes like a cat through water. Andromache’s face twisted; she felt the psychologs in her mind. Take them off! Take them off!

“Sister, sister—!”

Andromache swung on her, glad of the distraction from the psychs. She raised a finger. “Be quiet.”

Breseis recoiled at the pitched tone. Her mouth worked uselessly before peeping, “Yes.”

Andromache sped down the service corridor. Briseis stumbled after, lips working soundlessly, mind fluttering like a desperate bird in a pasteboard box. Andromache stopped at a door, placed an ear to it, and eased it slowly. This was dangerous: she’d nearly been caught more than once here.

Briseis whined.

“Come!”

Briseis came.

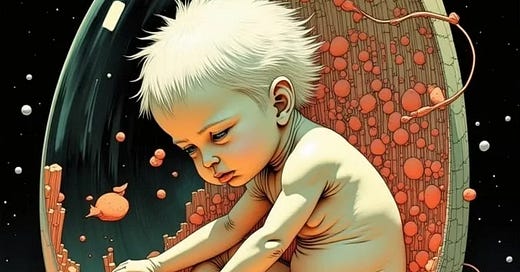

In deep niches in the white marble walls stood plasticine blocks with organ systems, nervous systems, and muscular systems, all in various stages of development: a museum of defleshed, deboned, de-organed, and disassembled and unfolded human structure from fœtal stage to puberty. Briseis had never been there: it was thought best to keep the girls away. Her eyes grew wider and wider, lips trembling, knees loose in horror. Andromache strode on, confident, down her coiling, careful path, silver hair gleaming in its braids. Not Chamber One, not Chamber Two, not Chamber Five nor Six—Chamber Seven. Wide, circular, polished concrete floor. Red lights low. A double ring of twenty glass vessels, and the faintest hum of power and fluid.

“Sister Andromache…not supposed to be here…this is for the fœtuses, not us…”

Andromache raised a finger.

Twenty clear glass vessels like eggs. The smell of antiseptic. The heat. Thin lines of light and faint flickering specks of amber, green, red, blue—small data screens with twitching leaping lines. Soft, encased lobed beds of dark pink tissue, and at rest in a warm, wet, dim world, a small form. Most were still as Briseis and Andromache crept around the tiers of tanks, each depending from tubes and pipes and tied cables, but one fœtus gently kicked the glass from within, and one flexed fingers and toes.

Andromache stopped at a tank, running her fingers over it. She gave Briseis a narrow look.

Briseis’s voice cracked. “Why?”

Andromache peered in at the folds of placental tissue like a silken royal blanket under pale heels, like the flesh of an oyster. Tiny fists, miniature lips parted, thin hair in a whorl. A pearl of a girl within. “Mine,” Andromache said.

Briseis’s mouth worked. “She belongs to the Investors.”

“She’s my sister.”

Briseis knelt and touched the data screen. “She’s an Andromache. Like you.” Her brow furrowed. “Why are you looking at an Andromache?”

“She’s my sister…”

“We are all good sisters together, no matter what we are. We are building a world. You must not be here. I have to get an attendant. I have to tell Teacher.”

“She’s beautiful,” Andromache crooned, as if she wasn’t listening. “She’s like me. Better,” she whispered.

Briseis didn’t think so, but the form curled in the glass tank was a baby, after all. “She comes out soon. She’ll get a wetnurse. We leave crèche in a few months.” She rose, shaken but more confident. “Our contracts will be sold. You need to be seen by a mentist. You need to be fixed. You need medicine, sister doula.”

Andromache drank in Briseis’s face. Briseis squirmed under the green eyes glittering. “Why are you here?” the First Girl insisted.

“I come to be with her.” Andromache brushed the tank delicately, as if she could stroke the locks on the baby’s forehead. “I help her. I’m making her even better than me.” She smiled at Briseis. “And I’m very good, sister doula.”

“You are not good,” Briseis said, stubborn, “Teacher will take you to the mentist. Your mind is wrong. I knew there was a problem! I knew!”

Andromache considered, polishing the finger marks from the glass.

“I need medicine,” she said slowly

“Yes!”

“The attendant can help us.”

“Yes, sister.”

“Take me.”

Brave Briseis faltered. “I have not been in here by night,” she said. “It’s scary, sister…I don’t want to see the bodies again.”

“I know the way.”

Briseis slipped her hand in Andromache’s. “You take me.”

Hand in hand, they went, circuitous, around Chamber Nine then Chamber Ten. An arched entrance and glass wall and glass doors opened at its side. Andromache, eyes and ears always open, fluttered fingers across the keypad and wiped it as it swung open.

“Sister, why are we going in here?”

“The attendant is in here,” Andromache said, and she darted back among white cabinets and counters.

“Sister!” wailed Briseis and, after a long hesitation, followed into the dark.

Lights flowed under fixtures, just enough glim to walk without stumbling, everything blue, gray, and black, floor freezing under her feet. She clutched her sandals.

“Andromache? Sister?” Everything smelled of medicine and disinfectant and rubber.

“Sister?”

In the distance, there was a faint scrape.

“Sister, I don’t think the attendant is here. I think this is the pharmacy.”

Tap, tap.

“Sister, I am afraid,” Briseis quavered.

Feet pattered in the distance.

Briseis thought of stories about things hiding in the woods to grab little girls who left the campus. She crept forward, towards a dim light behind a counter where a terminal must be drowsing.

Patter patter.

“Is—is that you, Andromache?”

The ring around Briseis’s neck was seized, choking.

“It’s me, Briseis,” Andromache said behind her.