Safiya is forty-five. She is sitting in the waiting room at Biosphere on Kulhanek Strato. She is reading the weekly Kolektiva Journal. There is an interesting article on hybrid citrus fruit designed to flourish on the regolith with minimal soils. There’s a black-and-white picture of the orange-lemon hybrid.

Biosphere comes up with these things. Ĉaŭŝo works for Biosphere, at its research facility southwest of Helioshad. When he comes to visit with his wife and children, every season or so, he talks about the things they are developing.

“We have the entire genome of Earth available,” he says. “Or at least all that they knew about or had left. Sometimes, things don’t quite fit, and we have to tinker with them.

He’s proud of his minnow. He had helped the mainframes build it. “It tolerates heavy metals,” he said. “They’re in the Oksidenta River.”

She didn’t think much of the Oksidenta River. It’s a ravine out of the hills of the same name on the northwest of Helioshad, opposite the Malglata, a barren range of red hills on the east side. Before humans came, the ravine was empty except for sudden seasonal downpours, but Biosphere has been nursing a steady flow which they think will someday reach the Yasindra, another alnost river that runs from the edges of the Upper Plateau almost to the sea. But now it has a minnow that her son helped make, Phoxinus phoxinus safiyae.

“Not everyone has a fish named after her,” Ĉaŭŝo says.

“I suppose not.”

Biosphere has the entire genome of Earth in its mainframes and is recording the entire genome of Iphigenia, which is easier (“There’s less of it,” Ĉaŭŝo points out,) and a lot harder (“We don’t totally know what parts of the native life are genes, or how they work. And it’s mostly in the sea”)

There’s something else Biosphere wants.

“They need our entire genetics, everyone alive, especially those of the first generation that are still alive, who landed here, and their children, before human biodiversity gets lost. They want a record of everyone.”

Need. Want. Safiya knows about things that are needed, things that are wanted. Things she’s wanted all of her life. All the food she could eat. All the hot water she could use. All the books she wanted to read.

She can help with this, though. It’s socially useful.

She reads the Kolektiva Journal. She waits for the nurse.

The nurse comes. She’s a pretty young thing, younger than Ĉaŭŝo or even his wife Ĝorĝeta, young enough to make Saifya wonder if she could even be out of school yet. She doesn’t want to ask.

“Hi, I’m Tanit,” she says. “You are—Safiya. Come back here!”

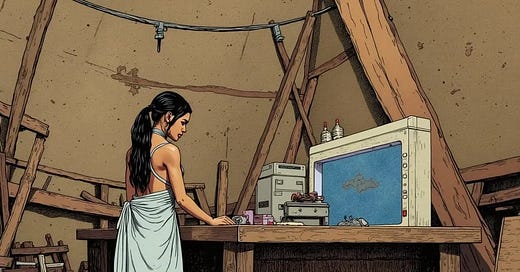

Back here was behind a wood and canvas wall, a desk made of scrap lumber, and a series of devices and storage. Safiya doesn’t think much of the girl’s breezy manner, or her sloppy pronunciation. Many of the younger people Safiya finds hard to understand. Tanit has a white shawl instead of a white coat. A lot of the younger people are starting to dress oddly, with wrapped clothing instead of jumpsuits, which makes sense; they are easier to make—who has time?—and cloth is a scarce resource and the climate hot in the summer. Safiya has thought about learning to make them. It’s apparently quite easy.

Tanit also wears a seashell on a string around her neck. Safiya has seen many of those and doesn’t know what it means, and no one else her age seems to either.

“What is that?” she asks.

Tanit touches it. “This? Oh! I don’t know, it’s about life. Spiritual, I guess,” she says vaguely. “It’s from the sea. Life comes from there, I guess?”

Safiya doesn’t think much of spirituality. It feels like a dying thing to her. Her father was still a Muslim but not much of one; no one had ever built a mosque, and Safiya now isn’t sure if anyone is still a good Muslim. It’s not like one can go on the Hajj from Tau Ceti, and the moons are no guide to Ramadan or anything. There’d been several churches in Landing, but no one ever got around to building one in Helioshad. The Hindu temple has an elderly man sweep it daily and take care of some images. That’s it.

Now, these shells, with no meaning. Or little.

Safiya sits down. The samples are quick to take. She gives six, and Tanit is happy. “Very helpful!” she says, labeling them. “Nothing will be lost this way!”

Safiya approves of that. She hates losing things.

“Thank you for coming in!” the nurse smiles. “It helps us build a world.”

“Of course,” Safiya says. She has to return to work now, and she’s already putting the DNA sampling out of her mind. So many things to do this week. One more done.