Rain in Gythion

Οὐρανία, πολύυμνε, φιλομμειδὴς Ἀφροδίτη, ποντογενής, γενέτειρα θεά, φιλοπάννυχε, σεμνή, νυκτερία, ζεύκτειρα, δολοπλόκε, μῆτερ Ἀνάγκης·

Ĝjang Nŭin came home from the Academy to the flat he shared with Mariposa. He had his rucksack on his back with his tablet and books in it, and a net bag with other things. Mariposa met him at the door.

“What do you have?” she asked hopefully.

He gave her the bag with a grin. “Milk!” she said. “Two milks!”

She gave him a hug and a kiss on his thin cheeks. “Two? How’d you get two?—You didn’t steal it, did you?” she asked, worried.

“Me? No! Not this time,” he said. He’d done it once and felt terrible about it.

“Why two? Was there a lot?”

He nodded. “A truck came from Gythion. There’s been rain, and the cows have more milk, and they could spare some for us.”

“Oh, thank god,” she said automatically. “No, thank Her,” she muttered. She opened and sniffed one of the paper cartons, and with a fingertip left a few drops of white at the base of a little wooden figure on the windowsill, a curved female figure on a seashell shaped out of old red pseudopine, the silica fibers polished to a sheen by daily attention.

Ĝjang wanted to tell her to thank the impersonal cycles inside Iphigenia’s climate that had chosen that spring, like a lazy engine, to finally turn over with a grunt and a windy, damp fart and produce rain again in the north, synching with the needs of the newly fertilized plains and new forests just before both of those died altogether. The grasses and the trees and the fields whose damp exhalations had thrown the winds off course.

The little wooden figures were common in the homes of their friends now, all the graduate proctors and intellectuals and guitar-strumming women with black hair and patterned dresses and their men wearing expedition gear even when they weren’t in the field. The rain girl, some of them thought, would bring luck or food. They even had a name for her. He’d heard but didn’t remember it. Mariposa knew he didn’t think much of the rain girl, and she didn’t share, and he didn’t ask.

Ĝjang shrugged at that. It was harmless, and he wouldn’t start a fuss. He went to the crib and picked up Miranta. She was so tiny still, so thin. Mariposa’s milk had given out almost before it began, so Miranta had scalded milk when they could get it, and boiled bone broth—fish bones, mostly—treacle, whatever they could find. She was six months old and looked three.

“You work for the Academy,” Mariposa had said angrily. “Can’t they do better for us?”

“If they do better for us,” he said, “someone else will starve.”

But today, two milks.

“Who’s my darling?” he said. “Who’s my girl? High-pressure air’s moving off the Upper Plateau, little wiggler, jet stream’s moving south again. Rain, sweetie, you might see rain!”

She whimpered hungrily.

He sat on the floor holding his daughter while Mariposa warmed milk for her, just a little, no need to waste it through a huge urp, then more a little later … and the flat was hot, and the wind was hot, and they had rain in Gythion but none, not yet, here.

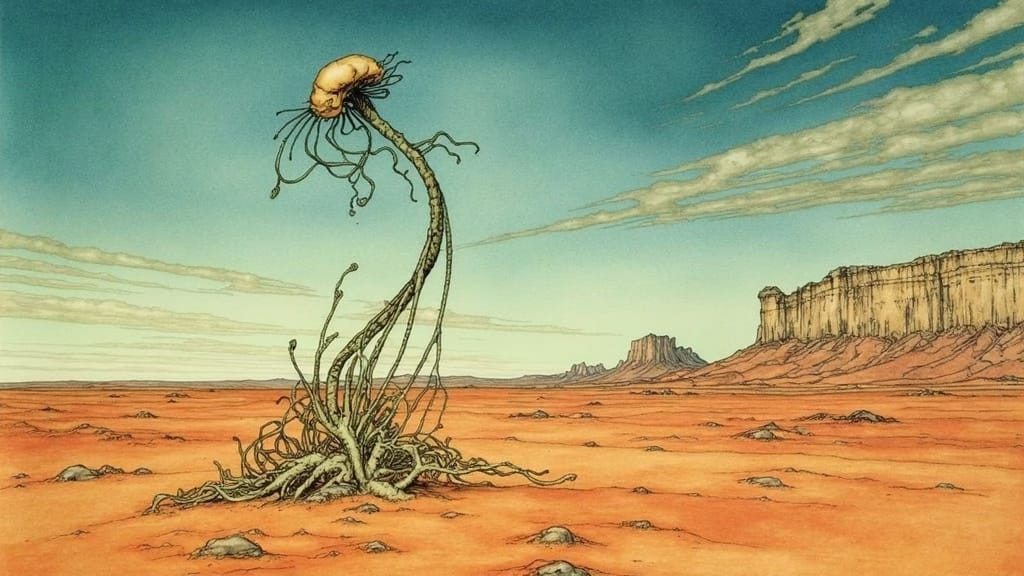

Champignons

The champignons grew in the sandhills with the bustle-leaves and the yellow-worts, and Daddy said they all three probably depended on each other in some way no one understood. They were tall as a house, taller, six, eight meters high, with broad heads, deeply cloven. Daddy said that the heads broke away when they seeded, shedding drifting sporelets acr…