Krisa Gyges’ eyes flew open, and she sat up, the blankets slipping off of her.

What happens today—what happens—oh!

“Da,” she said, breathing deeply. “Da comes back.”

She swung her feet to the cold plank floor and got out of bed, and reached to shake the slumbering form next to her. “Zghira,” she whispered. “La, Zghira. Wake up.”

The girl sighed, and rubbed her eyes. “Ah,” she sighed. “Morning already?”

“Already.”

“Mm, yes, Miss.” Zghira yawned and poured water. They washed their faces. There was bread, and jarred fruit from Hipassus, and butter. The cows were lowing, and must be milked.

“Come on, dress me.”

Zghira hastened to wrap on Krisa’s chiton and peplos and girdle, and ribboned Krisa’s hair before hastily dressing herself. They donned their boots and headed across the springy lichengrass to the byre. Soon, streams of milk sang into buckets.

“Krisa!”

Krisa half-turned. “Mum?”

Her mother leaned through the byre window. “I need milk for the children.”

She handed through a pitcher, and Krisa filled it, squirt, squirt, squirt. “There, Rosy-Wreath’s finest. Is Kypris down here, then?”

“Yah, just got here. Going to help with what your da brings in, and help me with the garden after.”

“Should I get the girls on the sluice then?”

“Yes, but everyone comes up when the truck arrives.”

“All right.” She handed the pitcher back.

Sunlight flowed ruddily through the Athenavista peaks when they drove out the cows, who eagerly crossed the ford to the meadows Da carefully tended and spread for years before they ever dared bring cows here. “Call me the Biosphere Corps,” he had joked when Mum expressed doubt in the project, but three kilometers by five hundred meters of regolith above the wiry, inedible lichengrass was now a somewhat delicate hay meadow, supporting their tiny herd of three.

“That’s what we do, Krisa,” he told her one night as they walked through the swishing green grass, the native glow bugs still sifting up and glimmering in the cool air. “That’s why humans came here and what we’ve been doing ever since. Building a world. Here, a hay meadow. There, a forest. Over there, farmlands. But wherever we go, we take Earth with us.”

The cows roamed there now, fertilizing their domain, as the grass waved and and legumes fixed nitrogen into the nearly sterile soils. So too flourished the gardens at both ends of the Valley of Gold.

“We can buy all we need in Hipassus,” Mum said, “but…”

“But it is proper to be self-reliant,” Auntie Gem finished. “Just in case.”

Just in case.

The family saying. Krisa had heard it many times, and when she prayed, she prayed about the just in case quite often.

But today things would be good. Da returned today from Hippassus with Kypris’s husband Naresh. They had taken a bit of gold and would bring back a truckload of supplies. Krisa’s step bounced, and she smiled. Zghira smiled too, and kissed her on the cheek. “La, Miss, you look happy.”

“I am. I don’t like it when anyone’s away. It makes me feel…weak. I like everyone here together, working hard. You know?”

“Working hard is proper,” Zghira agreed. “And I will feel better when the men are back. That is proper also. Safer.”

“You sound like Auntie Gem.”

“You always say that.”

Krisa laughed, whistled a few bars, and then they came to the cross in the path. One way led to their house, the byre, and the big house, and one led to the lake house. The rightward way led down the valley. Krisa stopped there, and Zghira looked expectant. “Run, tell Polyxena what Mum said, and tell them to run the sluice until the truck gets here.”

“Should I help?”

“Yes. I’m going down the valley to wait for the truck.”

Zghira looked dubious. “As Miss pleases,” she said. “What would Miss Gemma say?”

“Auntie Gem would say do what I tell you.”

“Properly, Miss,” Zghira agreed.

“It’s my da, Zghira. I want to be first to see him.”

Zghira shrugged with a helpless smile.

“Yes, yes,” Krisa said. “You don’t know…”

Zghira took Krisa’s face in her hands and kissed her on the forehead. “He’s someone you wish to see more than anyone right now. As I wish to see you when my eyes open. Miss will wait,” she smiled, “we will work.”

She turned and hurried down the path, boots scuffing up the decades of ruddy brown dead pseudopine needles with a quiet susurrus.

Krisa ran the other way, in the speckled sunshine falling across the Athenavista mountainslopes and through the stiff glassy needles of the pseudopines. The trail was slick and sliding with fallen needles, but she had run this path down the valley since she could walk.

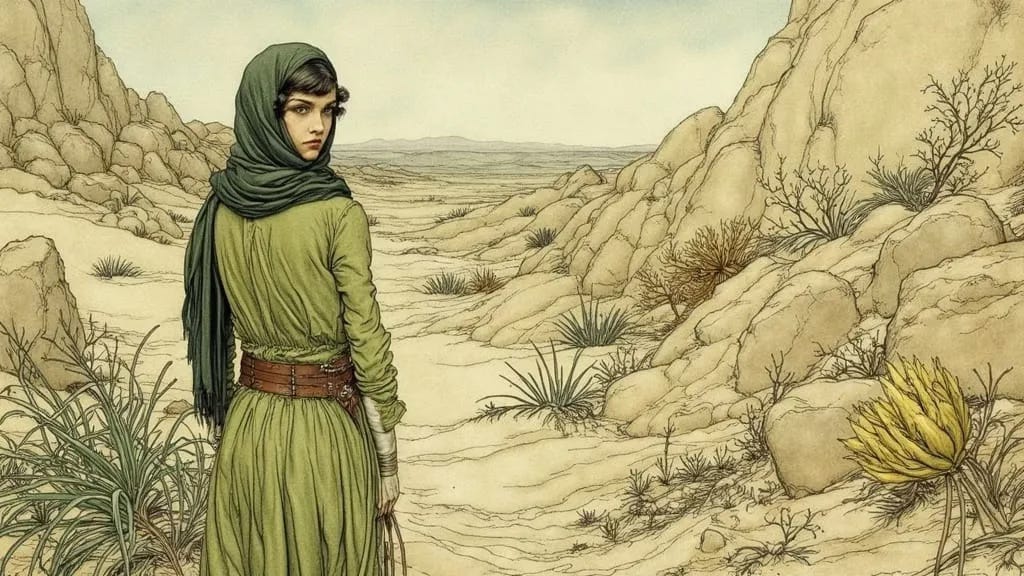

She was twenty-six, would be twenty-seven when winter began blowing out of the Upper Plateau. She was tall and strong and wore her black hair wrapped and ribboned on her head. She left behind the trees, and the dry, prickly lichengrass slopes lay open, the faint wheel-path of twenty-seven years of trips out of the valley, across the stonelands, and into Hipassus.

Krisa had a face already weathering, brown hands marked by pale scars. She could run all day, and even at five had run lunchpails and tools from one end of the valley to the other, and climbed the bluffs to the diggings, and raced all the way home.

Smart like her mother, patient like her father, strong like both, Christophia Gyges ran and ran and ran.

The valley widened, the lichen grass thinned: even the native stuff needed water, and the valley’s inner lawns became patchy among the stones and gullies until they disappeared altogether. The stream faded, soaking into the bottom of a ravine, vanishing into stands of thousand-year-old glassy reeds. She took the height, passing through the Pillars, and waited on the ridge-end, fanged with yardangs.

She sat on the rock where she’d first waited alone for Da when she was seven. She’d waited half the day under a sheet of canvas to keep the sun off, and drank nearly all her vinegar and water. He’d picked her up and hugged her and given her a stuffed animal from the town. “La, Krisa,” he had said, “My big girl!”

She waited again, arms wrapped around her knees. The sun crawled out of the peaks ten kilometers above, hot white, tinged orange, hanging in the crisp aqua sky.

She put her hands across her brow, squinting. In the stonelands she thought she saw a puff of dust. Dust-devil? Heavy breeze? Mirage? Anything was possible out there.

Her back was to the Valley of Gold, and that was home. Out there were the hostile stonelands, and the lifeless desert, and the town of Hispassus Mum hated. Krisa had been many times. There were too many people, hundreds of them, and the walls shut the sky out and the streets were dusty.

“You should see Clytemnestra,” Mum said. “It’s prettier, and older, a city made of salt by the sea.”

“Take me there some time!”

But Mum shook her head. “Never. I will never go back.”

And she fingered the ring of brass around her neck.

There was a puff, a regular puff, and Krisa leaned forward. She smiled, jumped to her feet, rocking back and forth. Over the flats, slowly through the stones, towards the Pillars, and she was running, waving, her boots sending dust flying, chiton and shawl fluttering, down the ridge, shouting.

The rocking green-and-rust truck stopped, the flywheel whining down, and the cloud of dust flew away. The door popped open and he stepped out.

She threw her arms around him.

Da.

I'm always lured into your stories by your tantalizing images.