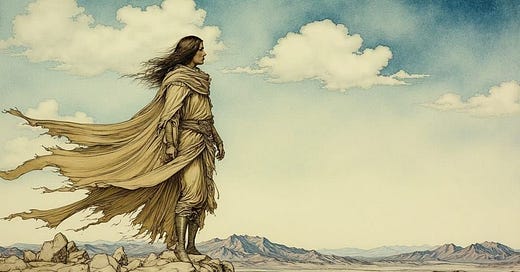

Krisa Gyges stood on the bluffs at the mouth of the Valley of Gold, looking into the Naiadara Valley. The wind was blowing strong, and the brown dusty plain below was showing signs of an early spring dust storm. She shielded her eyes, and patted her girdle, feeling the goggles there.

She wasn’t a tall woman, but she was a hard-working one. She got that from her mother, who she could never remember taking an hour off time during the day to lie down and rest, or a day to be ill. Krisa had been up before dawn, before even Da and Auntie Gem (Da’s wife) and Krisa’s mother were astir. She had put on her chiton and shawl and cloak and boots and puttees, left a note on the kitchen table, and walked fifteen kilometers down the creek to where it faded into stands of native marsh plants. The Athenavista Range was full of dawn behind her then as she looked over the tumbled stonelands to the plains of Hipassus, and the last stars were fading.

Below her she saw the prospectors’ camp.

She put her thumbs in her girdle and looked disapprovingly at it.

It was a disorderly place: a pair of canvas tents and a rattle-trap metaplastoc supply shed and a series of hoses to a reservoir they’d made by damming a spring. There was already a trash pile down the way, with empty cans of surplus militia supplies and who knew what all. She didn’t see an obvious latrine. A truck was parked in the shelter of a huge stone. It looked three hundred years old, about as bad as Da’s truck.

The whole business offended her sensibilities. Auntie Gem was painfully orderly in everything she did, and Mum tried to imitate her, and Da—though a man and naturally lazy and disordered—was at least tidy enough for his sex.

“We don’t have things to waste,” he said, tidying his boxes of wire and fasteners. “Everything costs and I have to get it in Hipassus, and that’s a two-day drive. I have to know what I have.”

The prospectors were up. There were two of them, the old one and the young one. The old one had a white beard and a limp. The young one had no beard but wasn’t well-shaved. He had curly black hair. They puttered about, splashing water on their faces from the end of the hose, and opening tins of breakfast. She could see the puff of steam when they popped open. Her stomach growled: she had grabbed a slice of Mum’s bread, but then she’d walked fifteen kilometers in the dark.

The bearded prospector looked up, saw her, and gave a wave. He said something to the younger one, who turned quickly and waved, then beckoned.

Krisa frowned. She wasn’t worried about the limping old man, but the younger one—

This is my home, she thought, and ostentatiously checked Da’s militia dagger in its sheath on her hip, and walked slowly down, trying to look dangerous. The wind helpfully filled her cloak and she hoped she looked like Irodiada in her Huntress face, ready to turn a peeping man into a deer and set his own dogs on him.

She entered the untidy camp and stopped.

“Miss,” the old man said. “You’re from the settlement up the valley.”

Settlement? It wasn’t a settlement, exactly. She’d never thought of it like one. Her, her younger half-sister and her husband and children, and Da and Mum and Auntie Gem, and the four indentureds in their barracks who ran the gold-washer. A dozen people.

“Yes,” she agreed. “You know about us.”

“Yah,” he said. “We’ve heard of you.”

“My da’s retired militia,” she said, touching the dagger hilt. “He’s taught us things. He has guns.”

“No, I’m sure he has. I’m Artavax. You want some breakfast?”

She nodded. “Yes.”

“I’m Kasmiro,” the younger man said. “He’s my uncle.”

“Great-Uncle,” Artavax said, getting a white tin out of the supply shed. It said BREAKFAST. Militia didn’t bother to define what you’d get. It was always a surprise.

“I’m Christophia,” she said. “Christophia Gyges.”

Kasmiro smiled, as if it was a delightful birdsong. “Sit down,” he said, pointing at a wooden nail keg. “Water?”

“I’ll stand. I have a canteen.”

“Yah, yah.”

“Why are you here?”

Artavax gave her the opened tin. It was bread and eggs. She popped the wooden utensil out of the lid and speared a bit. It wasn’t bad.

“Same as you, gold.”

“This is our valley.”

“Well, true, Miss,” he said slowly, “but outside the bluffs I’d call this the stonelands. We didn’t come into the valley. We’re down here, and whatever’s washed out, I think we can look for, yah?”

“We aren’t fond of outsiders,” she said.

“I can understand that.” He tugged on his beard. “Out on the edges, eh, Miss? No aristoi. No militia.”

“No neighbors.”

“Well.” He put his hands on his hips and rubbed his nose. “We won’t come any closer.”

“I’ve lived all my life with no one closer. No outsiders but my sister’s husband, and the work-gang girls.”

“We’re good neighbors,” Kasmiro said, almost pleading. “We won’t even visit, unless you invite us.” He smiled, his curls blowing in the wind. The dust was beginning to approach, filtering through the stonelands.

“That won’t happen,” Krisa said. She ate the bread and eggs, and they watched her in silence. Finishing it, she put the tin and the utensil on the head of the nail keg. “I’m going home,” she told them. “I’ll know if you follow.”

Artavax nodded. She put on her goggles, pulled up and pinned her shawl for veiling against the dirt and their eyes, and left the camp. She felt, or imagined, Kasmiro watching her climb, looking at her legs and backside all the way up the bluffs to the path back home.

She didn’t look back.

A follow-up could be interesting! Them having indentureds semi-surprised me; it would be interesting to see the Gyges have a different practice of it. (OTOH, making them "good owners" invites comparisons with real-world minimization of harms.)

Common to your books is a more humanized and (sometimes dubiously) consensual romantic relationship involving indentureds and contract owners, though it's not clear that ever lead to more enlightened outlooks on the practice (Alcmene is really the only one with both the perspective and the opportunity).

I get the sense that Iphigenia is universally pretty conservative (though not a cultural monolith), and the "caste" system and the lack of questioning of it seems fairly in keeping with your Hellenic inspiration. You've mentioned that the wrong side won the war and I'm curious what remains of the losers, whether minority views or descendants.