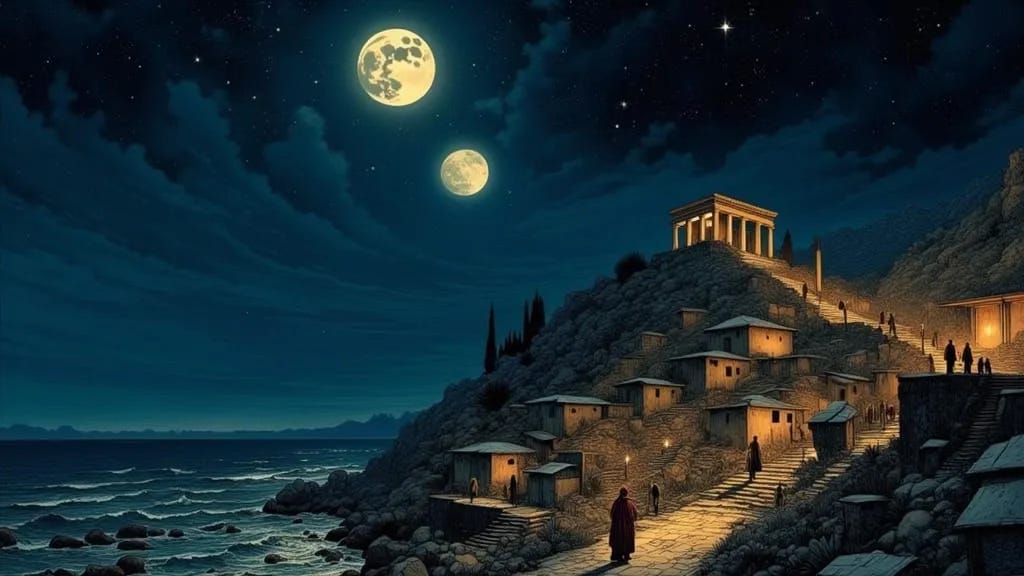

The door was good, but it was not good enough for me at midnight. It was not proof against whatever force gave me the will to walk. I walked in the night, barefoot through the vilaĝo, up the hill. Thyme and oregano grew in the cracks of the stones, and a warm wind was lush off the sea. My hair stirred, cropped beneath my ears, and I had dressed myself in one of Psamathe’s chitons, a pale white shift. A woman was by me, and she placed a wreath of the purple creeping thyme on my forehead. Up the hill they all walked, streaming, carrying wax tapers, the villagers did, dressed in white, and Psamathe and Rhodope with me. The servants hung close to me, and I heard their voices whispering in my ears, but it was only more music.

The chimes, the clappers, the lyre, the guitarina, they played them, the flautrino and the aulos. The vilaĝonos gathered at the temple, a broad semicircle on the lawn under the cypresses. The archon waited there, dressed in white with a square white hat with a red stripe, and a priestess, old, old, in white and gray, leaning on a stick, reminding me of the witch-woman in my childhood village, eleven light-years away.

They sang, and just then I could not speak or understand Ipjijenian, but it was a droning, drawing-out music—a music for seducing serpents and soothing beasts. I shivered at it, sensing the power and age in it, centuries of islanders in this remote place, under these blue-green skies, these strange moons, these seas swarming with the life of two worlds, never overlapping the other.

Tetidon mi vokas, kun okuloj ĉiel-bluaj,

Kaŝita sub velo de homaj rigardoj;

Granda Oceana-reĝino, vaganta tra profundoj,

Ĝojanta per ventoj dolĉaj sur la tero;

Kies benaj ondoj en rapida sinsekvo,

Frapas rokajn bordojn sen-fine fluas:

Ĝuante en maro serena ludi,

En ŝipoj triumfante kaj akvaj vojoj.

Matro de Irodiada, kaj de nuboj mallumaj,

Granda nutristino de bestoj, fonto pura.

Ho nobla Diino, aŭskultu mian preĝon,

Kaj faru bonvolan mian vivon via zorg’;

Sendu, benita reĝino, al ŝipoj ventan favoran,

Kaj portu ilin sekure trans ŝtormaj maroj.

The priestess raised her hands, and the song ended, and the music with it. Everyone knelt, even I, pulled down by clutching Psamathe and Rhodope.

“All life,” she said, “comes from the sea. On Earth. On Iphigenia. She is the Mother of all, the Mother of the Sea-Father, the Mother of Irodiada, born of foam. In her two worlds met and the Great Goddess arose, to find Temes asleep in the vines, his robes cast away. Grain spilled, blood spilled, seed spilled, life to the soil, life from the sea.”

The congregants echoed them, and I understood them, though my tongue still could not form their words. A fire of blue-green seemed to cover the roof of the temple, the edges of everything, danced on my tongue.

“There are deeps unknown off the land, and into them we cast things of beauty made by our hands on the holy days. But on the highest day of midsummer, the Sea comes to us, that we do not forget her, forget what She has created and given in gift. In times of old, the chair was filled, and those who could see the farthest and the clearest could assuage Her daughter’s ancient needs, and who could speak to the daughter of the deep, and see all roads and say all blessings. But for three generations, the iron seat has been empty, and so we must find our own way.

“Who here can speak to the Gorgona? Who here can see what must be seen? Who here can tell the fates?”

No one answered, and she called this out twice more.

“Then,” she said, “if none pass the test, then we must offer our daughters to the sea. Who has a daughter to offer?”

The archon, shuffling, beckoned, and a sun-browned and staring girl in a white shift was brought forward by a glum, rough man. Brass glinted around her neck in the taper- and torchlight. “I have a girl from my farm I can offer. She’s a hard worker. But the vilaĝo must not suffer for my stinginess.”

The priestess beckoned, and the girl stumbled forward. “Child, you win favor for Thisbos from the Sea. You will prevent the wrath of storm and sea-beast and fishless nets.”

The frail-looking creature blinked, her hands clutched before her, and she nodded miserably.

“Then She accepts—”

“Wait.”

The priestess, half-turned, and my dream flowed with the blue fire, and a pair of women walked out of it, or out of the temple, I could not tell.

“Who are you?” the old woman asked, querulous.

“I am a friend. I am Herme Scyros.” She was tall, bare-armed, bare-footed among that congregation, thyme-crowned, and her daughter behind her. “This lass,” she stroked under the chin of the farm-servant, “need not gift herself this season to the Sea. I have an offering I would make for the favor of the Lady.”

The priestess peered at Herme, and so did I, for the dream was falling swiftly away, and the vision-fires with it, and I began to realize that I, in very truth, knelt in the grass in front of the square temple on the hill, Psamathe urging me to flee.

“I offer that woman—her, with the hair cut short round her ears—and her two companions. I own the indenture on all of them. Though she wears no collar, she will soon. The blessed Queen sends to ships a favorable wind and carries them safely across stormy seas, and I ask Her favor for my trade.”

The farmer, his servant no longer in discussion, hastily left the scene with her as she wiped tears of relief from her eyes.

And I—I found myself rising startled to my feet, and the archon gestured as three men took us by the arms, though none truly were needed for Rhodope and Psamathe. I do not know what they could have done.

And what was there for me to do? Sleepwalking, I had come, dreaming I had come, and here I was now awake.

“On Sea-Day dawn, they will be ready,” the priestess said.

“On Sea-Day dawn,” Herme said smoothly. “Until then, they should be kept, like a treasure, in the Fortress.”

“So it is always done,” the priestess agreed. “The very pearl fallen from the stars kept there.”

And so, to our great dismay, we were taken away as the congregation sang. The archon’s men were encouraged to bind our hands by Herme Scyros and her daughter, and they did not hesitate to do so.

Oy!