The only way to get anywhere, he said to himself, was to go there.

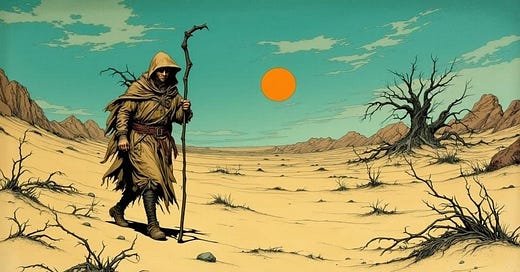

It was nearly inevitable, he thought, that he’d get nowhere. He was a thousand kilometers away from anything on the map with a name. The stretch of Plateau above him had no particular designation, and this entire plain below was called nothing either. This was not a human place.

It was a cold one, though, in the early morning. It might stay cold for a while. So down he trudged.

Walking downhill seemed easy for a while. Crunch, crunch, went his boots. Squeak, squeak, went his puttees. His toes struck stones, rolling and scattering them down the regolith with a tip-tap patter, tap-tap, tap-tip. He felt like he was making time. Easy.

Meter after meter, stride after stride.

Let’s say we’re taking a meter a stride. One stride a second, one thousand seconds to go a kilometer … sixty … into one hundred once … forty, drop the zero … sixteen, seventeen minutes a kilometer. Say seventeen. Seventeen thousand minutes to go a thousand kilometers …

He tried to do the math in his head and decided, in the end, it was a twelve-day walk anywhere if he never stopped.

Two weeks, to be realistic … but he had to stop. He had to sleep. It was cool up here, but he’d have to stay out of the day eventually. It would be murder by day, freezing by night.

A month. On half a bottle of water and a handful of dried apple chips.

Five weeks to be safe.

I think I’m going to die, he said to himself.

The first night, he wedged himself into a hole with a small xenosnake and shivered so hard he thought he would throw his back out. The second day, he began to realize that the staff he’d broken from under the air-car weighed ten kilos and was going to drag him to his death.

“Shit,” he muttered. He looked around. In the distance was a scrabbly bit of native vegetation just a few hundred meters away.

He hated to waste the steps on a lateral move, but he went ahead and walked them. The amount of water he had now was none, so he supposed it wouldn’t matter what he did. The amount of dried apple chips he had left was just one. He salivated at the thought of it —or it would have if he had any saliva left.

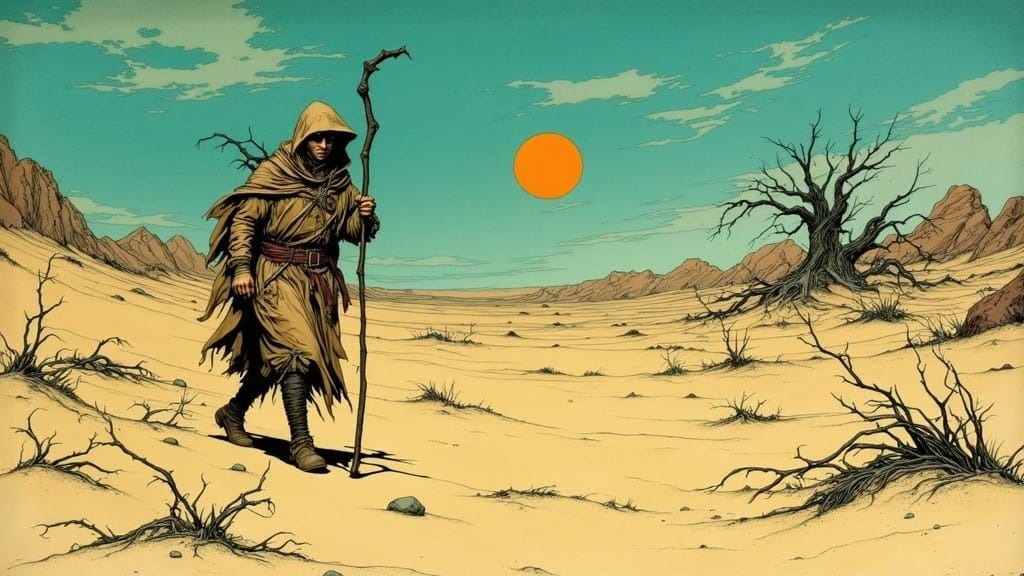

The native plants seemed dead, though that might have been an illusion. Iphigenian plants often looked dead. He looked closely. It didn’t seem to be wirewood. If it were, it would kill him slowly and agonizingly. He already had that on his list of things to do; there was no need to start that up quickly.

He rocked a thick, rigid spine back and forth slowly, flexing it on its root. Back, forth, back, forth.

It creaked and broke.

With a grunt of triumph, he jammed his metaplastoc staff into the regolith like a defiant trophy and hobbled on downhill with the lighter wooden staff.

Crunch, crunch, went his boots. Squeak, squeak, went his puttees.